In large processions the citizens of ancient Athens flock to the hill of the Acropolis. The magnificent sacred sites provide the backdrop to captivating celebrations. Gifts are laid down at the altars and bloody sacrifices take place. Life-like sculptures of heroes and gods crafted in marble and bronze surround the community of revellers.

The celebrations visualised the myths of Athens and kept them alive. Stories of vengeful gods, mighty kings, terrifying wars and tragic sacrifices accompanied the Athenians through the year. The myths unfolded around the city’s past and determined the identity of her residents.

Athena, the city’s patron and her son Erechtheus were particularly revered. The most important temples on the Acropolis, the Parthenon and the Erechtheion were dedicated to them. Still today once can sense the former magnificence of the prestigious architecture.

The imposing sacred sites were erected as part of a gigantic construction programme. The politician Pericles initiated this scheme ca. 450 BC. Persian troops had reduced the previous edifices to rubble. Together with the sculptor Phidias, Pericles developed his ambitious concept for the reconstruction: each temple, every decorative element and sculpture were to vividly illustrate to the citizens of Athens their culture and their history.

The exhibition at the Liebieghaus invites you to travel to ancient Athens to explore its visually stunning myths and sweeping festivities. Current research and theories present the sacred sites of the Acropolis in a new light.

The Destruction of the Acropolis

Tens of thousands of Persian soldiers landed on the beach of Marathon. The Persian King Dareios I. had dispatched his army to Athens around 490 BC, to destroy the city.

The Athenians were presented with an enormous military force, exceeding their own by far. However, the battle took an unexpected turn: initially the Athenians fended off the enemy.

Ten years later the Persians returned to attack the city, also as a revenge for their humiliation at Marathon.

After the devastating Persian attack, Athens is veiled in black smoke. The city and the sacred sites of the Acropolis have been demolished. Entire families fled to the Peloponnese peninsula.

Athens had suffered greatly under the Persians repeated attacks and their fierce destructive frenzy. The Athenians defended themselves. In the Battle of Salamis they defeated their attackers. By 479 BC they had managed to expel the Persians from Attica. Subsequently Athens rose to be the leading maritime power of Greece.

Upon their return to their city, the Athenians began – hesitantly at first – the reconstruction. Many years went by before the Acropolis shone in new glory.

A Great Construction Programme

The devastated Acropolis reminded the Athenians of the time of expulsion. An entire generation was traumatised by the attack. It is likely that Pericles, the politician, also experienced the devastation in his youth.

Pericles became one of the most influential politicians of Attic democracy. With great eloquence he secured the public’s support for the reconstruction of the Acropolis. But it was not his persuasive power alone that formed the basis for his great success; Pericles could also rely on the wealth of the major power Athens.

After the Persian wars several Greek cities had formed the Delian League – an alliance against the Persians. Money that the allies paid to finance defensive purposes, backed the cultural heyday of Athens.

Together with the sculptor Phidias, Pericles conceived of the most visually imposing construction project of all times. The Acropolis was to rise as a symbol of the city’s triumph.

A Myth Comes to Life

The meaning of the Acropolis’ new pictorial scheme is enigmatic. Numerous approaches have been made to decipher the representations.

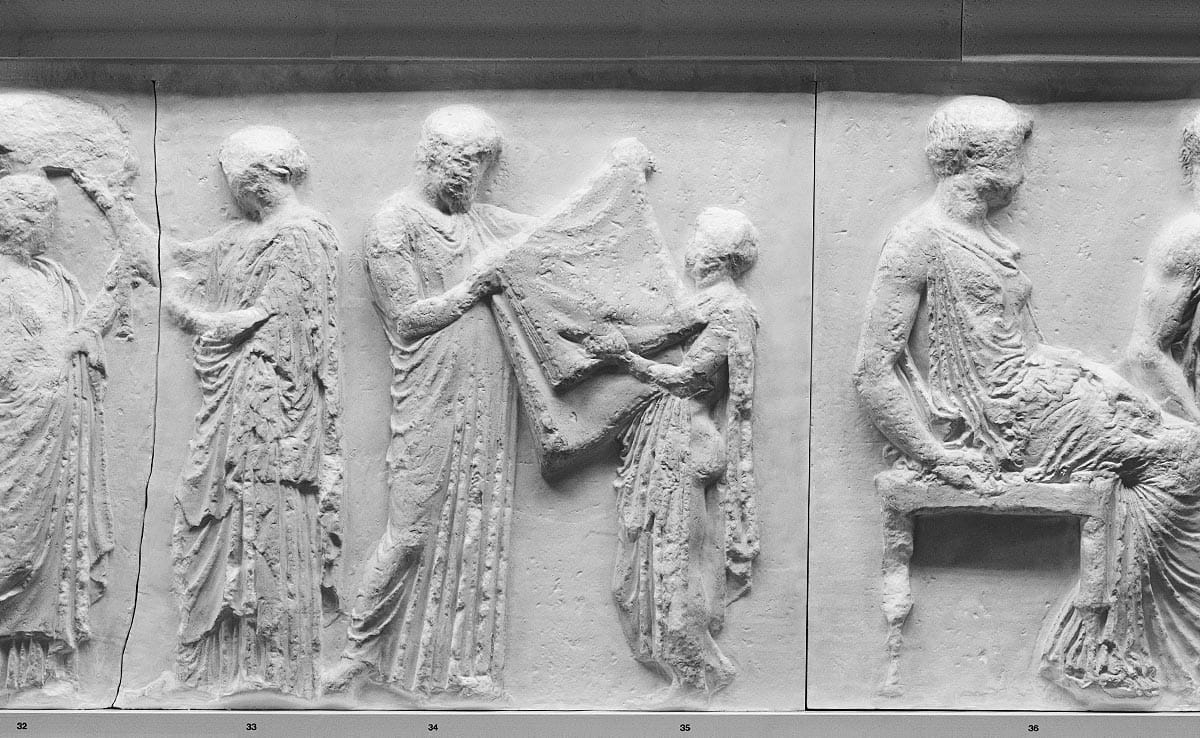

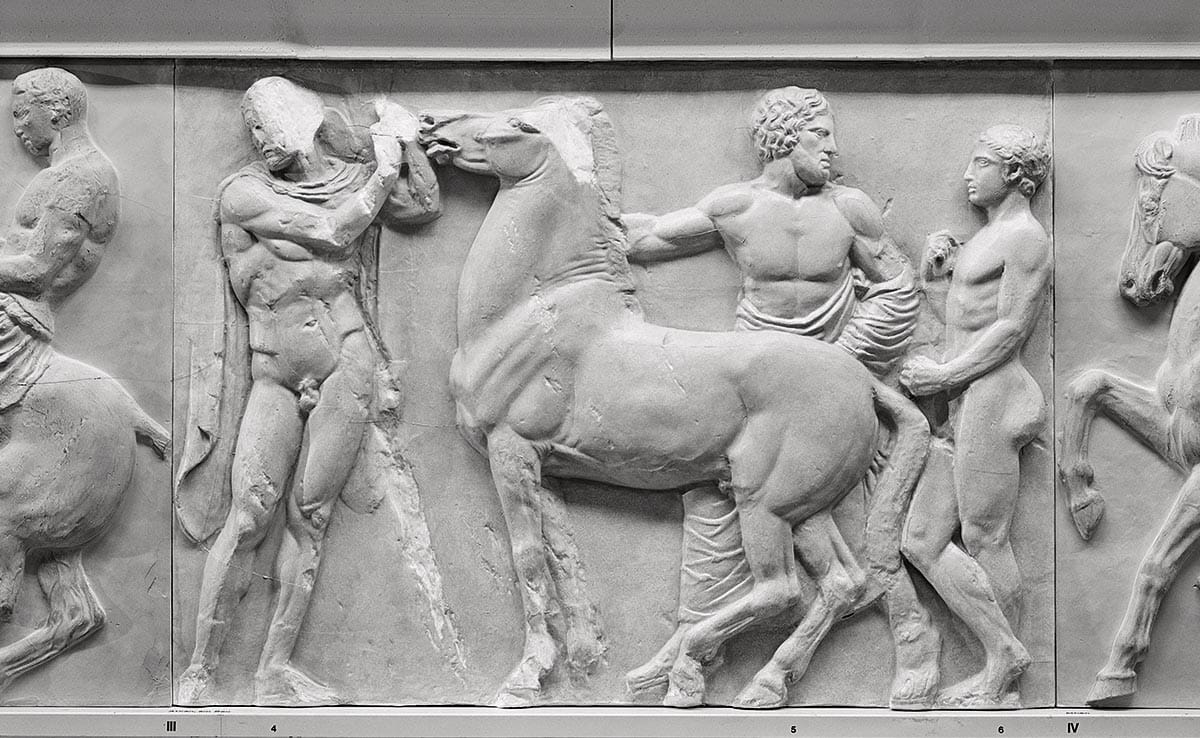

What are the stories the famous Parthenon Frieze narrates? The 160 m long relief strip runs around the entire Parthenon. The most varied festivities of the Attic calendar are represented.

Arisen from the Head

The goddess Athena is the focus of this picture story. Already her birth is exceptional.

Athena’s father Zeus rules Olympus. His numerous liaisons are often fateful. He seduced the nymph Metis, who falls pregnant. She is expecting a son and a daughter. The father-to-be is prophesied that his son will challenge his rule. This prompts Zeus to devour his lover together with his two unborn children. He begins to suffer from unbearable headaches. In despair he turns to the god-smith Hephaestus, who takes a heavy axe and splits Zeus’ head. The present gods watch with amazement as Athena springs from his head in full armour and ready to fight.

The Chaste Goddess Athena

When Zeus devours his lover, the foetus of his unborn daughter travels to his head, from where it is eventually born. Metis, representing wisdom, must die. However, her intelligence and her spirit are preserved in her daughter. Athena is the patron of the arts and sciences, but also goddess of strategy and battle. The eternally chaste beauty is born in full armour.

Battle of Gods

The ambitious Athena and her uncle, the quick-tempered god of the sea and horses Poseidon compete for the patronage of Athens.

Whoever presents the country of Attica with the better gift, was to become ruler of Athens. Poseidon strikes the ground with his trident and a source rises. Athena plants an olive tree, providing valuable olive oil and wood – a present, which requires the inhabitants of Attica’s diligent care. The gods elect Athena as victor. Foaming with rage, Poseidon floods the land.

Their sons continue the battle of Athena and her uncle: Eumolpos supports his father Poseidon’s claim to the Attic land.

Erechtheus, King of Athens and son to Athena was his adversary. But how was it possible for the virgin goddess to have a son?

A King is Born

When the god-smith Hephaestus is asked to craft new body armour for beautiful Athena, he uses this opportunity for his advances. However, the virgin goddess refuses him. She takes a bit of wool, wipes his sperm off her thigh and throws it onto the earth.

Gaia, goddess of the earth receives Hephaestus’ seed. Nine months later she gives birth to Erechtheus. She presents her son to Athena wrapped in a cloth, the Peplos.

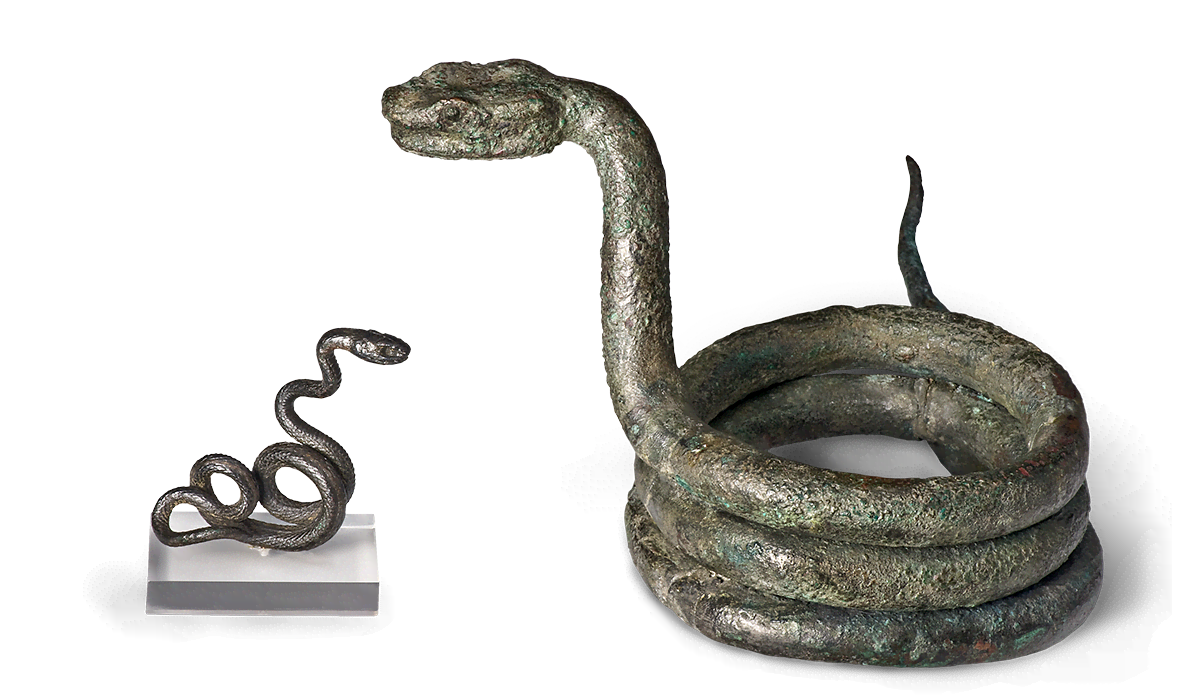

The story of Erechtheus forms the basis for the most important cult of the Athenians. Erechtheus has been chosen to rule Athens and the Attic land. His predecessor, the mythical first King Cecrops in the body of a snake, has been born from the earth, like Erechtheus.

Cecrops embodies the Athenians’ notion of being a native long-established people without ancestors. The allegory of the snake, dwelling in rock crevices and caves symbolises the common origin of all Athenians as earth-borne.

A Happy Childhood

Athena raises Erechtheus. Legend has it that she built a great house for her foster-son: the Erechtheion.

Indeed there was an old cultic site on the Acropolis. It had been destroyed in the Persian wars. As part of their construction programme Pericles and Phidias envisaged the most magnificent edifice on the Acropolis of all in this spot.

A long sculptural strip embellished the Erechtheion. Remains of the once colourfully rendered figures survive still today. They relate a happy life of Athena’s offspring: a boy on his mother’s or wet-nurse’s lap. Two children are enthralled by their game of dice.

Poseidon’s Revenge

Erechtheus grows to be the King of Athens. He marries Praxithea, with whom he has six daughters. However, the family’s happiness is not to last, as Poseidon is planning his great revenge.

To avenge his humiliation from losing against Athena once and for all, Poseidon dispatches his son Eumolpos against Athens. The King of the wild Thracian people together with his great army sets forth from the city of Eleusis. Poseidon’s belligerent move culminates in the Eleusinian-Attic war. In his mother’s name Erechtheus defends the Athenians and their city.

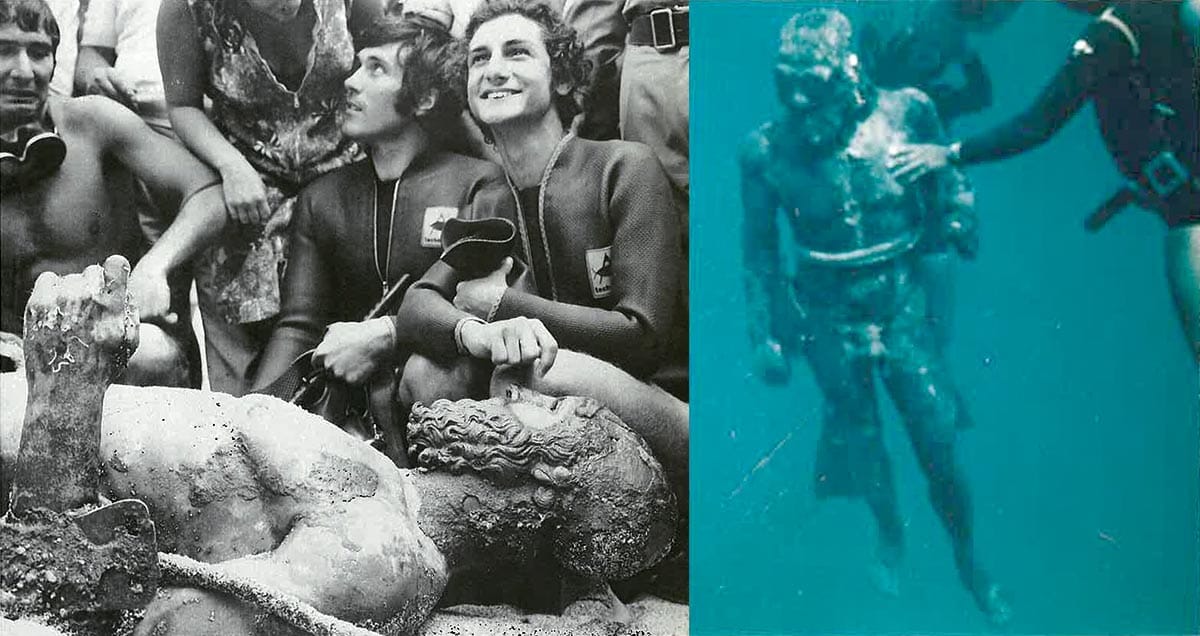

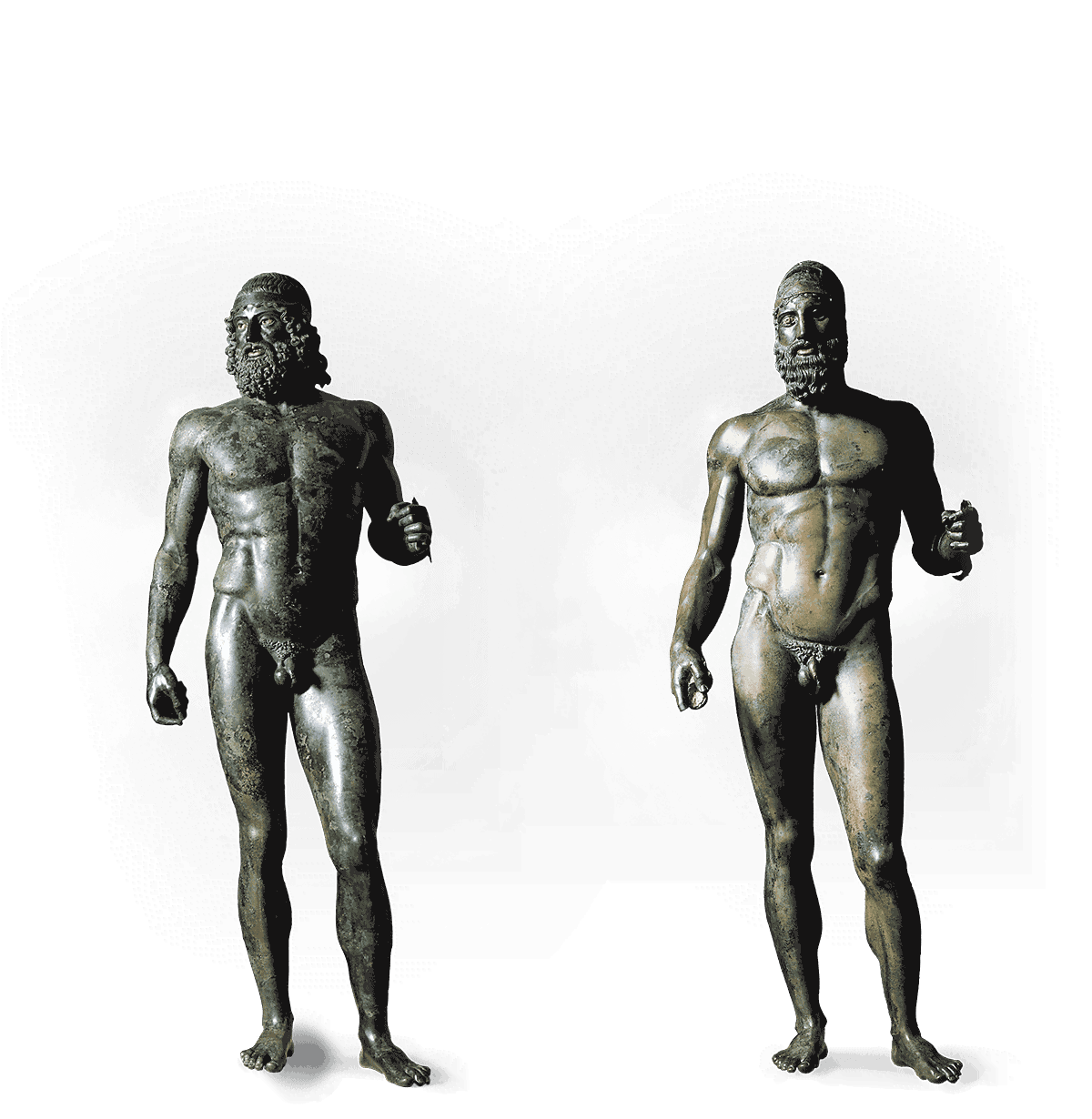

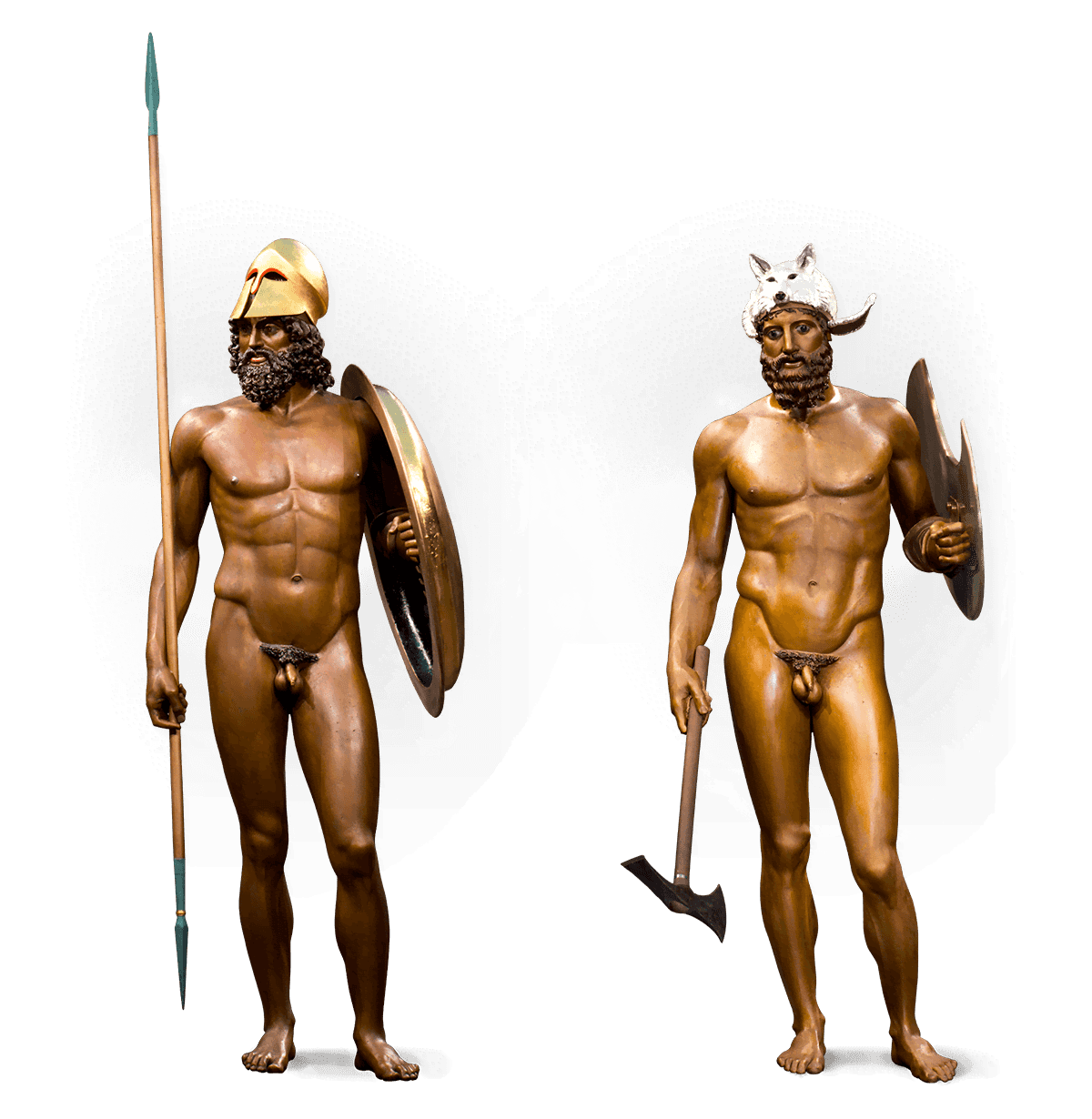

The Warriors of Riace

The two metre tall statues represent Erechtheus and Eumolpos, the adversaries of the Eleusinian war. Perhaps they once stood on the Acropolis, as reminders of the final battle.

In the course of examining the bronze figures the curator of this exhibition, Vinzenz Brinkmann, made an astonishing discovery:

„By Athena’s temple […] there are bronze statues of men, who stepped apart to fight. One they call Erechtheus, the other Eumolpos.“

Pausanias’ travelogue (ca. 115–180 AD), 1.27.4, trans. by Vinzenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann 1

A Cruel Sacrifice

The Athenians barely manage to resist the siege of Eumolpos’ troops. In despair, Erechtheus turns to Apollo, helper in need at times of war, for advice.

To emerge victorious from the Eleusinian war, Erechtheus and his wife Praxithea are forced to take a monstrous decision: they follow the godly council and sacrifice the eldest of their six daughters.

“I love my children, but I love my father’s city even more.”

Excerpt from the fragments of the tragedy “Erechtheus” by Euripides: Praxithea’s Speech 2

Together the sisters leave their parental home. Offering cups in their hands, they proceed to the ritual sacrifice of virgins.

This scene has been captured on the South side of the Erechtheion. There, six figures of girls carry the open hall’s roof. Shrouded in fine robes Erechtheus and Praxithea’s daughters appear.

When the eldest is to die at the altar, two more decide to follow her and take their lives. The eldest sacrifices her life for the salvation of the city and her inhabitants. The loss of two more children breaks the parent’s hearts.

The sculptures of the girls might have been embellished with delicately crafted snake bangles around the arms. They refer to the virgins’ origin, their earth-borne father Erechtheus, King of the Attic people. In the belief of the Athenian’s snakes appear as a symbol of the transition from life to death.

Erechtheus’ Death

The sacrifice of the virgin turns the Athenian’s fortunes in war in their favour. In the decisive battle, Erechtheus manages to overcome and kill his adversary Eumolpos.

Poseidon’s wrath over his son’s death is infinite. In a final act of revenge he plans the annihilation of Erechtheus together with his brother Zeus. Zeus’ divine thunderbolt paralyses the King of Athens. Poseidon picks up the King’s rigid body with his mighty trident. Raging with anger he rams it into the ground by the entrance to the Erechtheion right into the rock of the Acropolis.

In memory of the mythological battle a few slabs are missing in the floor of the hall in the Northern wing of the palace. In the ceiling a whole to match has been left open. This is where according to legend, the sea god’s giant trident hit the ground!

Sacrifice and Reconciliation

Hit by Poseidon’s trident, Erechtheus tumbles into the great depths of the mighty rock below the Acropolis. Magically he continues life in the shape of a giant castle snake. The earth-borne returns to the soil.

Athena in mourning finds solace and is mollified by the rebirth of her son. Violence and sacrifice form the basis of the reconciliation of the adversaries Athena, Poseidon and Erechtheus. To represent the peace the Athenians had the idea of merging the former enemies. The divine power unfolding in this union, was bestowed by the altar of the Poseidonerechtheus at the centre of the Erechtheion. The power Athens was reinforced by the war in the long-term. Adopting the god of the sea sealed Athens’ claim to maritime rule, too.

The sisters who died together with her present the immortal Erechtheus and divine Poseidon with wine and fruits: an idyllic scene in the netherworld.

Erechtheus and Praxithea’s three surviving daughters behold the peaceable scene. They are holding hands and are reminders of the story’s reconciliatory end, which had begun with the competition of Athena and Poseidon.

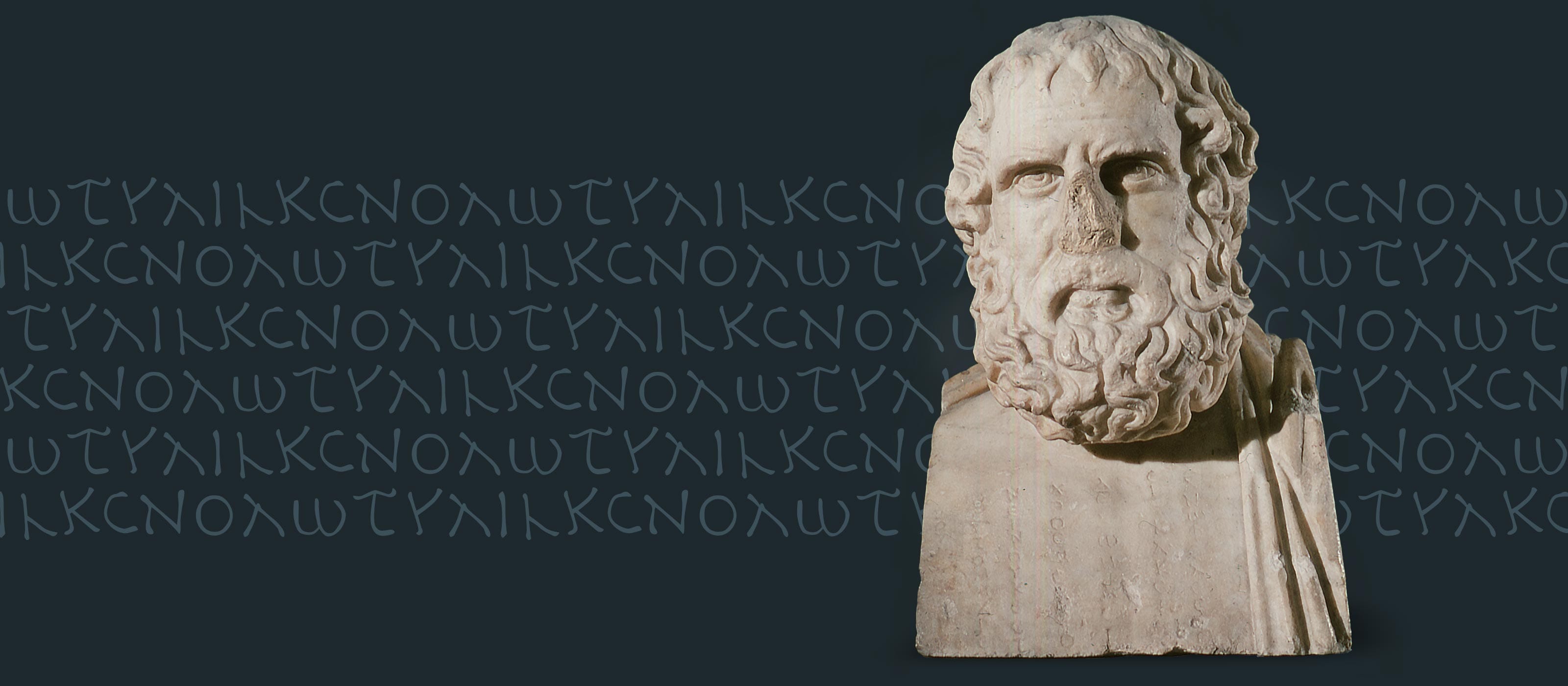

Personal Hint

The tragedy of “Erechtheus” by Euripides

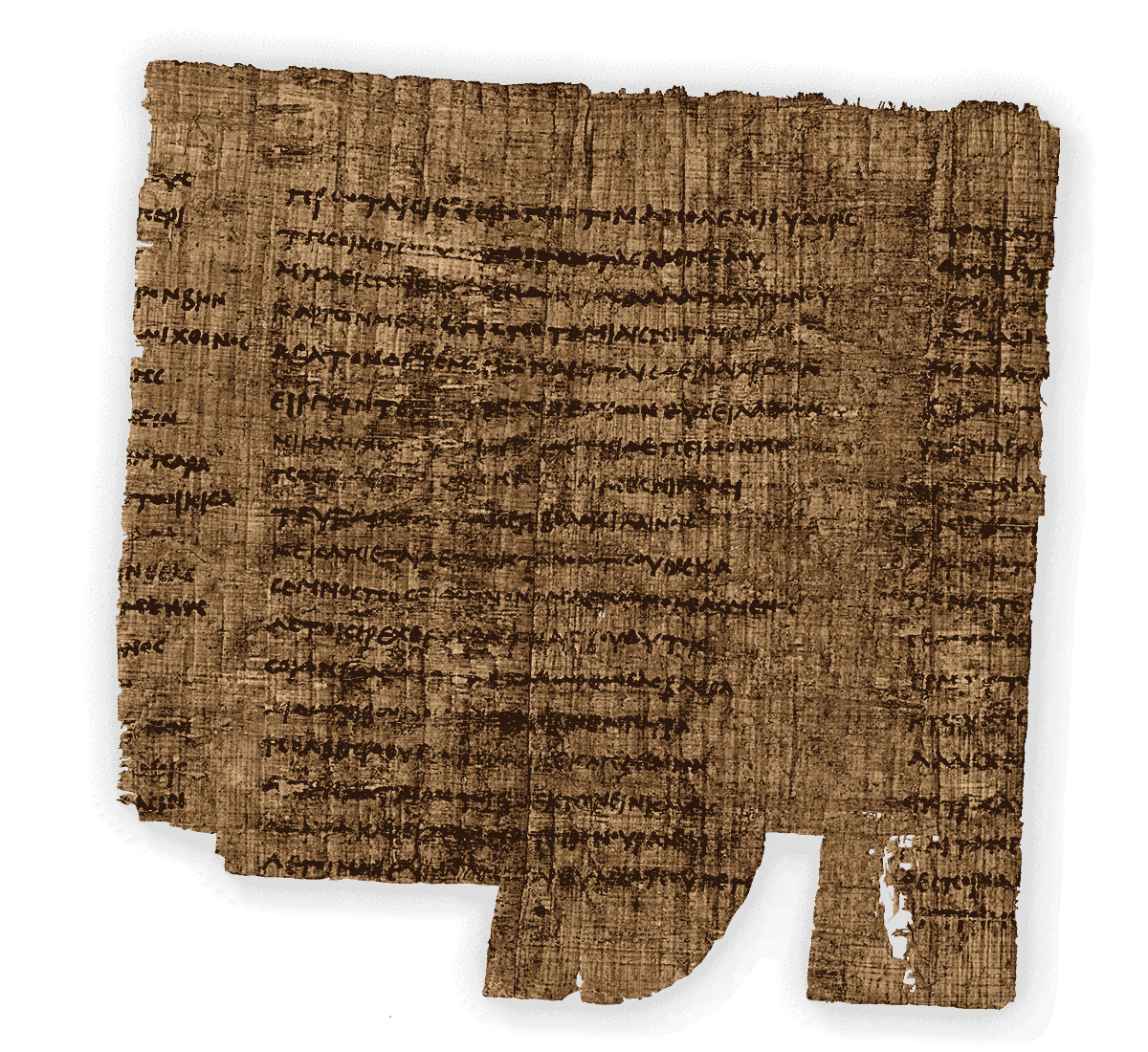

When Pierre Jouguet and his team excavated several mummies in a former graveyard in Egypt in 1901, they had no idea what a great treasure they had actually discovered.

The cases of the mummies consisted of several layers of glued papyrus. Only in the 1960s researchers succeeded in separating the individual layers without harming them. At last the text with which they were inscribed became readable. The papyrologist Colin Austin recognised fragments of Euripides’ tragedy “Erechtheus”, which had been considered lost.

It can be assumed that Euripides’ play premiered ca. 422 BC at the Dionysus theatre on the Acropolis. The tragic plot shows that misfortune cannot be prevented, even by the greatest sacrifice. Praxithea consents to sacrifice her child to rescue her city. However, in the end she loses three daughters as well as her husband Erechtheus, the King of Athens.